Flexi-wings and why they could be F1's biggest battleground in 2025

Aero elasticity is by no means a new weapon in the Formula One designer's arsenal but it is one that has to be regularly sharpened in order to fit within the bounds of the prevailing regulations.

As such, we often find that teams suddenly seem to steal a march on their rivals, as they better understand how to take advantage of the wing’s deformation to improve the overall performance of their car.

In 2024 we saw this battle fought on two fronts, with both the front and rear wing thrown under the ‘flexi-wing’ spotlight.

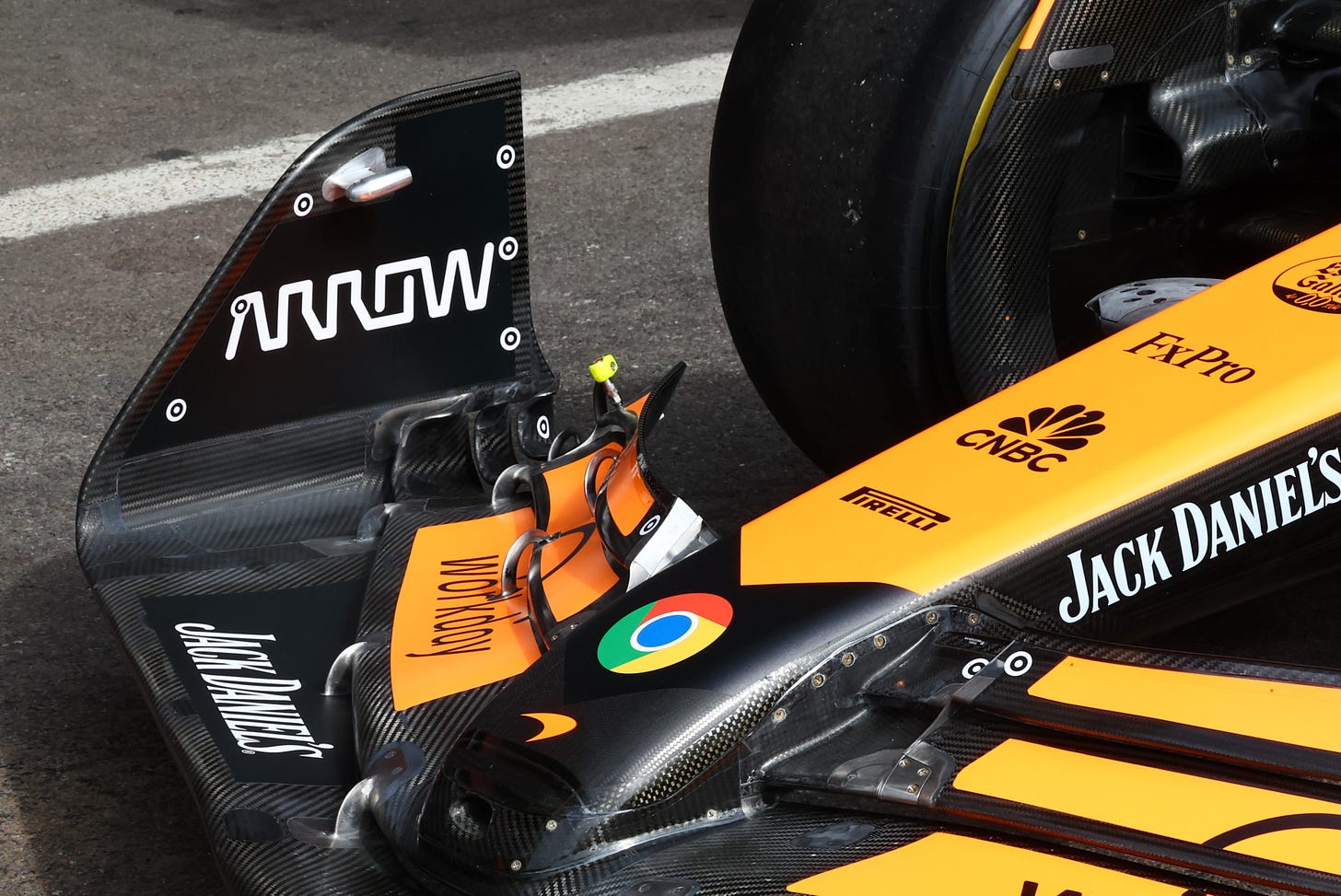

And, in both instances it was McLaren right at the centre of the debate, with their rivals seeking to reign them in via political means first, rather than make advancements behind the scenes that might be costly if the FIA were to intervene.

Red Bull and Ferrari were successful in lobbying the FIA in regard to McLaren’s ‘mini-DRS’ solution when it was discovered at the Azerbaijan Grand Prix, even though the governing body had initially given the team the green light to continue using it going forward.

Furthermore, the regulations have been altered for 2025 to prevent anyone from creating a similar, albeit less potent version of the solution*.

Where they were less successful was with the front wing though, as they firmly believe that McLaren’s solution helped to tip the scales in their favour and offered a significant advantage compared with their own designs.

The FIA did take a look at the situation though, with the governing body reviewing additional footage captured by a dedicated onboard camera from the Belgian to Singapore Grand Prix.

In this instance, teams were selected at random to fit a hi-speed camera that had been specified by the FIA in the housing attached to the nose in FP1, with reference dots also added to the front wing flaps and endplate to ensure that the deflection could be seen in the footage and studied thereafter.

The FIA had opted for a multi-race assessment period in order that they could capture information in regards to different downforce configurations, with their aim more about learning how each of the teams were using flexible elements to subvert the static load tests.

The issue for the governing body is that there’s no catch-all method to prevent this behaviour, as each team appears to be doing something a little bit different than the rest.

Of course, the most obvious flexion occurs with the upper flaps, as they fold rearwards under load, something that can be observed from the regular onboard footage.

However, the FIA appear to be happy with the amount of flexion that’s occurring here, with this less about non-linear deformation and more about how much the team is prepared to allow the flap elements to back-off in order to reduce drag and improve the cars balance between low and high speed scenarios.

"One of the challenges in the front wing is that, compared to other parts of the car, the front wing loading is much more varied between cars in a given location and so on.

So most tests relate to the load of a certain direction, certain position of application, certain magnitude must not produce a [certain] deformation.

On the front wing, the variety between cars would make that quite difficult." - Nikolas Tombazis, Single Seater Director, FIA.

This suggests that there’s non-linear deformation occurring on some, if not all, front wings up and down the grid, with each design tailored to finding performance in conjunction with the shape and aerodynamic profiles of the given assembly.

Therefore, creating a catch-all test is nigh-on impossible, just as it has been when the team have ventured down this path in the past.

In those instances the FIA has usually responded by increasing the load applied when the static tests are conducted during scrutineering. However, ramping up the load seemingly won’t improve anything here and so there’s no plans to do so for 2025 and with an all-new design being introduced for 2026 the game changes once again anyway.

This creates an opportunity for the chasing pack, as they now know the rules of the game, having assumed that certain criteria had previously been considered off limits due to their experience of flexi-wing designs and the technical directives that had ensued in the past.

For example, there was a fascinating difference in opinion in what worked best in the 2010-2013 front wing flexi-wing era, with McLaren opting to pitch their wing front-to-back under load to better align with their wing’s characteristics, whilst Red Bull appeared to droop the entire outer portion of the wing closer to the ground.

We’ll not get onto Ferrari, as they struggled to get it working for the longest of times and their wings were often seen fluttering, rather than having progressive flex. But, suffice to say, every team was flexing their front wing to one degree or another, until the FIA stepped in and altered the load tests once more.

However, it’s this difference in deformation that makes it difficult for the FIA to intervene, as what they consider to be a solution might benefit one team and hamper another.

In order that this isn’t the case, they’ve opted not to throttle one particular design avenue and instead make it more of a development choice for the teams on which is best to chase for their exact requirements.

For the teams themselves though, some feel aggrieved there hasn’t been some sort of action, as it delayed their own response last season and effectively baked-in a latency in terms of development for those that already had the solution on their cars.

That two month period between the Belgian and Singapore Grand Prix was essentially limbo for the likes of Red Bull and Ferrari, as they either had to commit development resources to a design that might be banned shortly thereafter, before it even goes on the car, or find themselves further behind the curve.

And, as Fred Vasseur points out below, chasing that development can also be detrimental to both present and future projects

“We had the discussion with the story of Red Bull two years ago, is that it's not because you are burning half a million, that is half a million out of 150 million,” he added.

"It's half a million out of three or four millions of development, because you have your guys, you have the racing costs, you have this, this and this and at the end, you have the development, and you have X millions of development.

"But it's a small X, and if you burn for nothing half a million, you can't spend somewhere else. And for sure, that's when, for me, it was more than on the edge the story."

In Ferrari’s case they clearly decided that they had to at least put some effort into a parallel development program during that period, in order that they didn’t find themselves even further behind if the solution did get the green light, which of course it did.

Therefore, albeit not of a new specification that warranted being listed on the car presentation document, it’s understood that Ferrari introduced a more flexible front wing variant at the United States Grand Prix.

Meanwhile, Red Bull also clearly had eyes for something similar during the back end of 2024, once they had word that the FIA wasn’t set to intervene.

“Is something acceptable or is it not? If it’s deemed to be acceptable, then obviously that encourages you to pursue similar solutions yourself.

“So I guess they’re collecting that data. But yeah, it’s one of those things, as I say, that if it’s deemed to be acceptable, then you pursue that route.” - Christian Horner

Given the difference in the construction of the front wing for this generation of car there’s still considerable design divergence up and down the grid, which is why we’re likely seeing something similar to the 2010-2013 battle emerging, as there’s no one right answer to the unsolvable Rubik’s cube.

For the most part, how those differences emerge will come down to the inner and outermost sections of the wing, not the more visible movement of the two upper flaps that most fans seemed concerned about.

These areas of the wing offer a more critical change in how the airflow and vortices have an impact downstream, with the outwash generated in the outer portion of the wing perhaps more important, as it will influence the floor’s performance at the outer edge too.

It’s why we’ve seen a widespread adoption of the semi-detached flap arrangement, with teams now having at least the rearmost element, allowing them to curl the tip section more aggressively.

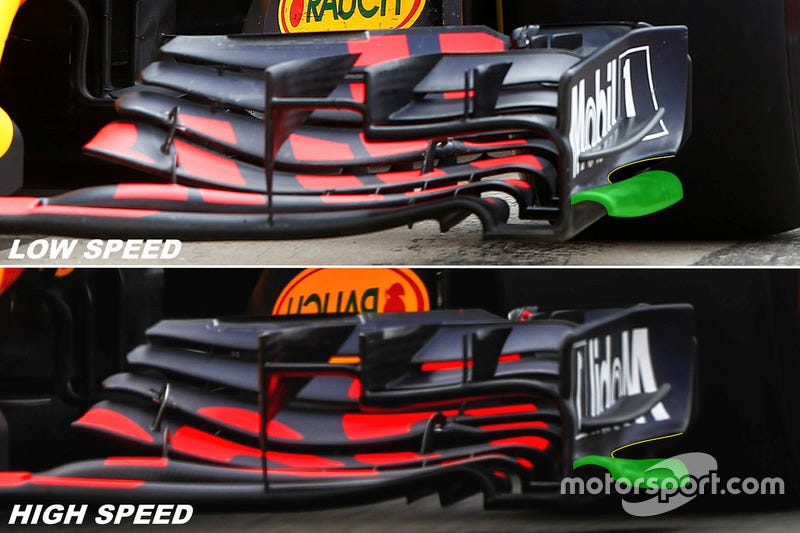

Comparing the RB20’s design (above) with the MCL38’s (first image) we can see that Red Bull only have the rear element with a spar between it and the endplate, whilst McLaren have designed the latter three flaps in order that they have the semi-detached and rolled layout.

Moreover, given these elements are disassociated from the mainplane it’s likely they have a different response to the load imparted on them when the car’s in motion.

Let’s take Red Bull’s flexing endplate and footplate design from 2017 as an example for how that might alter the flow structures in that region.

The stage, as they say, has now been set then, as the teams will all work on improving the behaviour of their front wing and increase the working range of their car for 2025.

This could lead to an interesting technical battle at the start of the season, as they all vie for position and attempt to make up the ground on the teams that had a head start on the development front.

*

iv. The distance between the two sections must lie between 10mm and 15mm at their closest position.

Furthermore:

c. At all points along the span, the rear wing profiles (as defined under Article 3.10.1) must have a minimum gap of between 9.4mm and 13mm. This will apply when the DRS is not in the state of deployment (as defined under Article 3.10.10) and will be measured with a spherical gauge.